- General

- Distribution

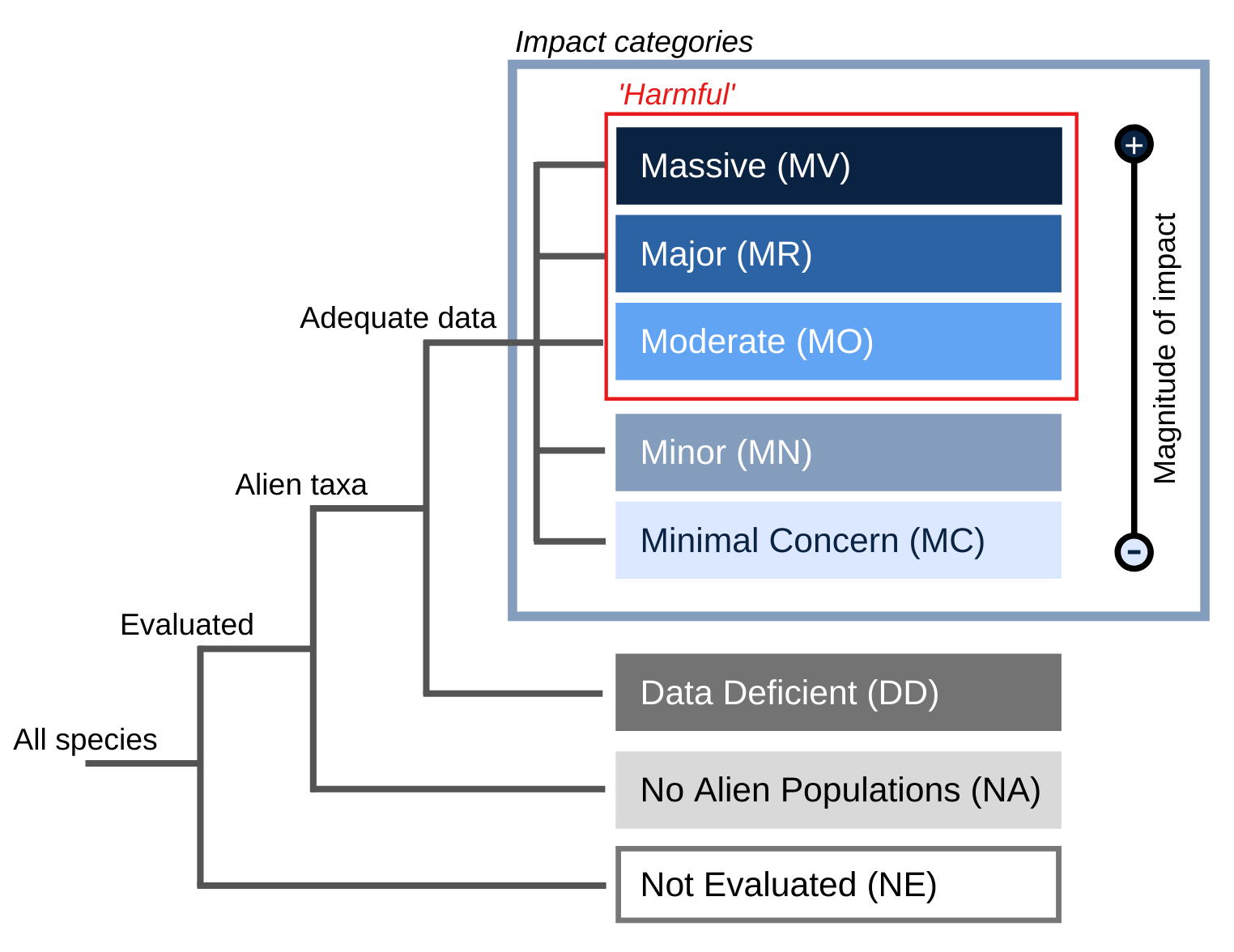

- Impact

- Management

- Bibliography

- Contact

Bufo strumosus , Court 1858

Bufo agua , Clark 1916

Bufo marinis [sic] , Barbour 1916

Bufo marinus , Mertens 1969

Bufo marinus marinus , Mertens 1972

Chaunus marinus , Frost et al. 2006

It has been estimated that less 0.5 percent of cane toads toad eggs survive to maturity. It takes a year for the toads to reach maturity, when they will be about 75mm long. Cane toads survival in the wild is unknown, but unlikely to be more than 5 years. Animals kept in captivity are estimated to live 10-40 years (Honolulu Zoo).

Cane toads were used for pregnancy testing in humans. A woman's urine was injected subcutaneously into the lymph glands of a male toad, resulting in spermatazoa becoming present in the toad's urine if the woman was pregnant (Berra, 1998 in Lever, 2001).

The cane toad is opportunistic in its feeding habits and will consume almost anything that it is able to catch (Zug and Zug, 1979 in Lever, 2001). Terrestrial arthropods make up the bulk of the diet, but snails, crabs, small vertebrates (mammals, birds, lizards and frogs), pet food and human faeces may also be consumed (Lever, 2001). Cane toads will gorge themselves if food is in abundance. Unusual items that cane toads have been observed eating include rotting garbage, a coral snake (Micrurus circinalis), fledgling birds and a lit cigarette butt (Lever, 2001).

Principal source: Lever, C. 2001. The Cane Toad: the history and ecology of a successful colonist. Westbury Publishing, West Yorkshire. 230pp.

Gautherot, J., 2000. Bufo marinus. 2001 James Cook University.

Compiler: IUCN SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group

Updates with support from the Overseas Territories Environmental Programme (OTEP) project XOT603, a joint project with the Cayman Islands Government - Department of Environment

Review:

Publication date: 2010-05-26

Recommended citation: Global Invasive Species Database (2026) Species profile: Rhinella marina. Downloaded from http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/species.php?sc=113 on 29-01-2026.

Toads have been implicated in the decline of populations of monitor lizards in Guam (Jackson 1962, Dryden 1965). Pernetta and Watling (1978) consider that the toads do not interact with native frogs because they use different habitats; the frogs are either along stream banks or in the foliage of dense forest. Villadolid (1956) found rats and mice in stomachs of toads in the Philippine Islands. Hinkley concluded that this toad is “economically neutral” because it consumes both “harmful” and “beneficial” invertebrates.

Secretions from the parotoid glands are produced when the toad is provoked or localised pressure is applied, such as a predator grasping the toad in its mouth (NRM, 2001). The toxic secretions are known to cause illness and death in both domestic and wild animals that come into contact with toads, such as dogs, cats, snakes and lizards. The toxin causes extreme pain if rubbed into the eyes (NRM, 2001). Human fatalities have been reported, but are probably confined to people who deliberately concentrate the toxin and then ingest it.

Overall, the major impacts are on predatory species that attempt to eat toads and then die; in particular, species that normally specialise amphibians, such as Mertens water monitor in northern Australia.

Physical: Cane toads can be excluded from garden ponds and dams by a 50cm high barrier, such as a thick hedge or a wire mesh fence. Toads may be killed humanely by putting them inside a plastic bag or container and placing them in a freezer (Brandt and Mazzotti, 1990).

Biological: In 1994, the CSIRO Division of Wildlife and Ecology (Australia) was assessing the pathogenicity and specificity of viruses against cane toads. Scientists at the CSIRO Animal Health Laboratory in Victoria have been searching for biological controls of cane toads and in 2001 they began investigating gene technology as a mechanism of control. Environment Australia have launched a project for the development of a cane toad biological control. The aim is to develop a self disseminating viral vector to disrupt the development of the toad. Scientists at the University of Adelaide (Australia) have isolated a sex pheromone in a native Australian frog; they hope that a similar pheromone will be found in cane toads that could be used to disrupt the breeding cycle. These are long term solutions.

Scientists at Sydney University have identified a parasitic worm that attacks the cane toads' lungs, stunting their growth and, in most cases, killing them. They believe the parasite has the potential to reduce toad populations dramatically.