- General

- Distribution

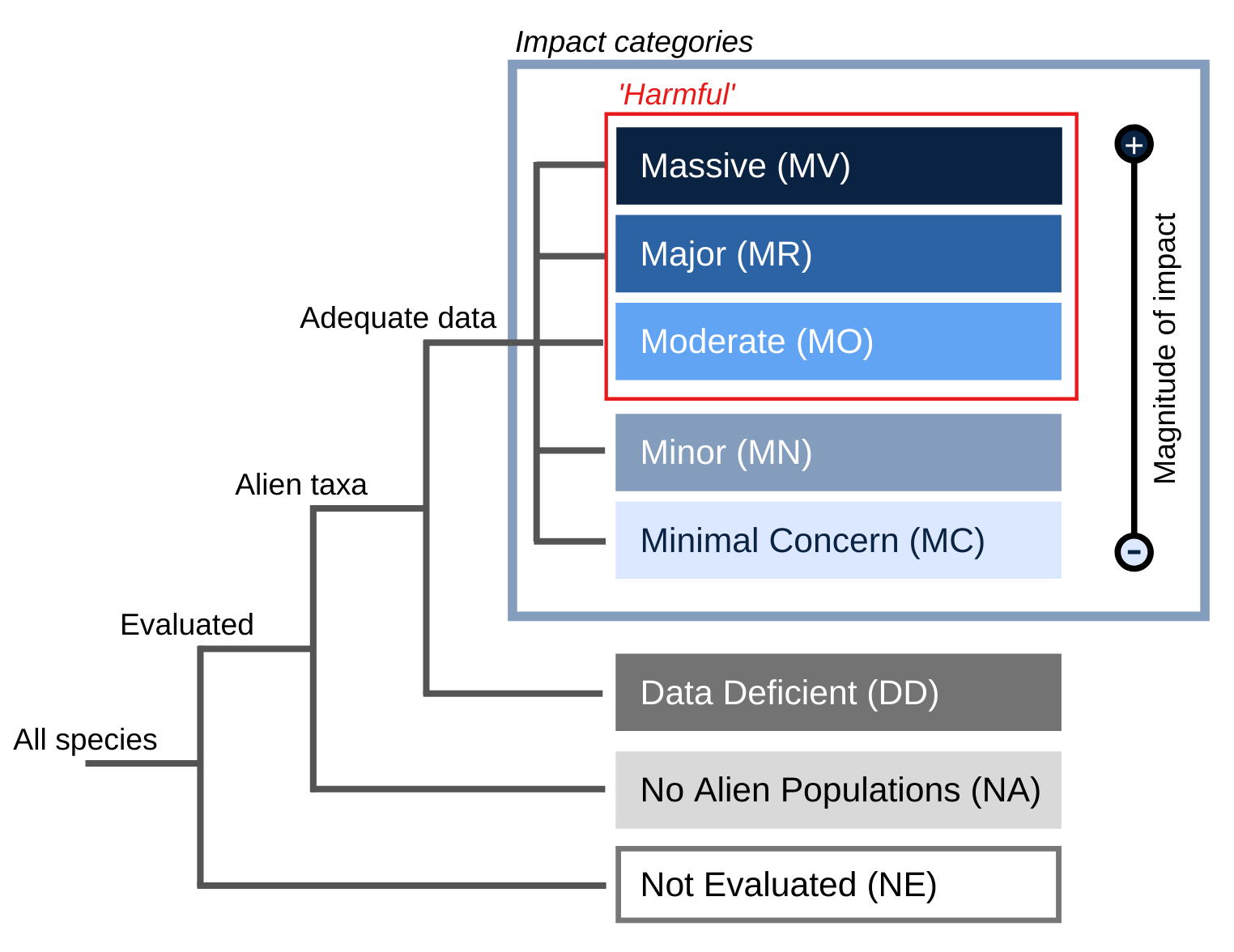

- Impact

- Management

- Bibliography

- Contact

Solenopsis saevissima , var. wagneri (Santschi)

Please click on AntWeb: Solenopsis invicta for more images and assistance with identification. The AntWeb image comparison tool lets you compare images of ants at the subfamily, genus, species or specimen level. You may also specify which types of images you would like to comare: head, profile, dorsal, or label.

Please see PaDIL (Pests and Diseases Image Library) Species Content Page Ants: Red imported fire ant for high quality diagnostic and overview images.

Please follow this link for a fully illustrated Lucid key to common invasive ants [Hymenoptera: Formicidae] of the Pacific Island region [requires the most recent version of Java installed]. The factsheet on Solenopsis invicta contains an overview, diagnostic features, comparision charts, images, nomenclature and links. (Sarnat, 2008)

In general, invasive ants are usually more likely to establish in disturbed habitats, including the edges of forests or agricultural areas (Ness and Bronstein 2004). Deforested areas are particularly at risk of becoming colonised by red imported fire ants (Morrison et al 2004). S. invicta constructs earthen mounds for the purposes of brood thermoregulation, which are easier to build in open, sunny areas; so it is less abundant in, and in general poses a smaller threat to, densely wooded forest habitats (Tschinkel 1993; Porter and Tschinkel 1993, in Morrison et al 2004). Tropical regions that are warm and wet, but also densely forested do not represent a suitable habitat for fire ants (Morrison et al 2004).

Principal source:

Compiler: IUCN/SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG) with support from the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF)- Biosecurity New Zealand

Updates with support from the Overseas Territories Environmental Programme (OTEP) project XOT603, a joint project with the Cayman Islands Government - Department of Environment

Review: Neil Reimer, Ph.D. Plant Quarantine Branch Chief Hawaii Department of Agriculture

Publication date: 2010-10-04

Recommended citation: Global Invasive Species Database (2025) Species profile: Solenopsis invicta. Downloaded from http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/speciesname/Solenopsis+invicta on 17-11-2025.

There is conflicting evidence as to whether S. invicta inhibits the dispersal of ant-dispersed plants. In some cases, it may interrupt and reduce dispersal by competing with native ant dispersers, eating seeds whole or in-effectively dispersing seeds (ie: by leaving them exposed on the soil surface rather than protecting them by seed-burial). S. invicta may increase or decrease the survival of plant, depending on the species and other biotic variables. They may benefit a plant by killing, or at least deterring, insects that damage the plant (such as plant-feeding insects). Alternatively, or in addition, they may reduce numbers of insects that benefit the plant, such as plant mutualists that protect the plant or disperse plant seeds or carnivorous insects (that prey on plant-feeding insects). In fact, S. invicta is a notable example of an invasive ant which has negative effects on such insects, because it prefers a protein-rich diet (Ness and Bronstein 2004).\r\n

S. invicta reduces biodiversity among invertebrates and reptiles, and may also kill or injure frogs, lizards or small mammals. In particular the red imported fire ant has the potential to devastate native ant populations (McGlynn 1999). It is competitively dominant to most other invasive ant species; it has displaced the Argentine ant (Linepithema humile), but not Monomorium minimum, in areas in the USA where the species have been introduced (Holway et al. 2002). In the USA, it has been found to negatively impact at least fourteen bird species, thirteen reptile species, one fish species and two small mammal species (through predation, competition and/or stinging) (Holway et al. 2002). The current economic impact of S. invicta on humans, agriculture, and wildlife in the United States is estimated to amount to at least half a billion, if not several billion, dollars per year (Thompson et al. 1995, Thompson and Jones 1996, in Morrison et al 2004).\r\n

S. invicta may impact social and economic activities at all levels. They can sting people and may cause an allergic reaction. Public areas such as parks and recreational areas may become unsafe for children. They may infest electrical equipment (such as computers, swimming pool pumps, cars or washing machines) becoming a nuisance, or even a danger, to people. Agricultural impacts may include damage to crops, interference with equipment and the stinging of workers in the field. The costs associated with S. invicta in the United States, for example, have been estimated at $1 billion per year (Pimentel et al. 2000, Tsutsui and Suarez 2003). The Australian Bureau of Agriculture Resources Economics has estimated the losses procured in rural industries to amount to more than AU $6.7 billion over 30 years. According to a professor at the Texas Agricultural Extension (USA) the agricultural economic losses caused by the ant are an estimated US $90 million annually. In Texas at least US $580 million was spent in 2000 to control this pest. Gutrich et al. (2007) undertook a study to estimate the potential economic costs to Hawaii, in case of the introduction and establishment of the red imported fire ant. The authors of the study conclude that the estimated impact on various economic sectors in Hawaii would be around US $ 211 million/year. \r\n

\r\nClick here for Information about the relation between colony structure and level of threat

Integrated management: The potential of invasive ants to reach high densities is greater in human-modified ecosystems; this is particularly evident with respect to land that is intensely utilised for primary production. For example, the little fire ant (Wasmannia auropunctata) is a great problem in areas in its native South America that have been over-exploited by humans, including in sugarcane monocultures and cocoa farms in south Colombia and Brazil, respectively (Armbrecht and Ulloa-Chacón 2003). Similarly, the Argentine ant (Linepithema humile) reaches high densities in agricultural systems such as citrus orchards (which host mutualistic honeydew producing insects) (Armbrecht and Ulloa-Chacón 2003; Holway et al. 2002). Improved land management, including a reduction in monoculture and an increase in the efficiency of primary production, may help invasive ant prevent population explosions (alleviating the problems caused by high densities of ants) and could reduce potential sources from which new infestations could occur.\r\n

Biological: Parasitic phorid flies have been introduced to control S. invicta. Multiple species of these parasitic flies (originally from Argentina and Brazil) have been released by researchers at the Brackenridge Field Laboratory (BFL). The fly larvae develop inside the ants and kill their host. Pseudacteon tricuspis, was introduced to several locations in Texas beginning in 1999 with BFL in central Austin. Flytraps have been used to map the spread of the first species of phorid fly introduced. It is found that the inrtroduced phorid flies have spread to more than 12 counties and 3.5 million acres in Central Texas and seven counties and 1.5 million acres in the Coastal Bend region of Texas, speading at 3 to ten miles per year from the initial introduction areas. Two other phorid flies have been introduced since 2004. For more details please see Using phorid flies in the biocontrol of imported fire ants in Texas.\r\n

For details on preventative measures, chemical and biological control options, please see management information.