- General

- Distribution

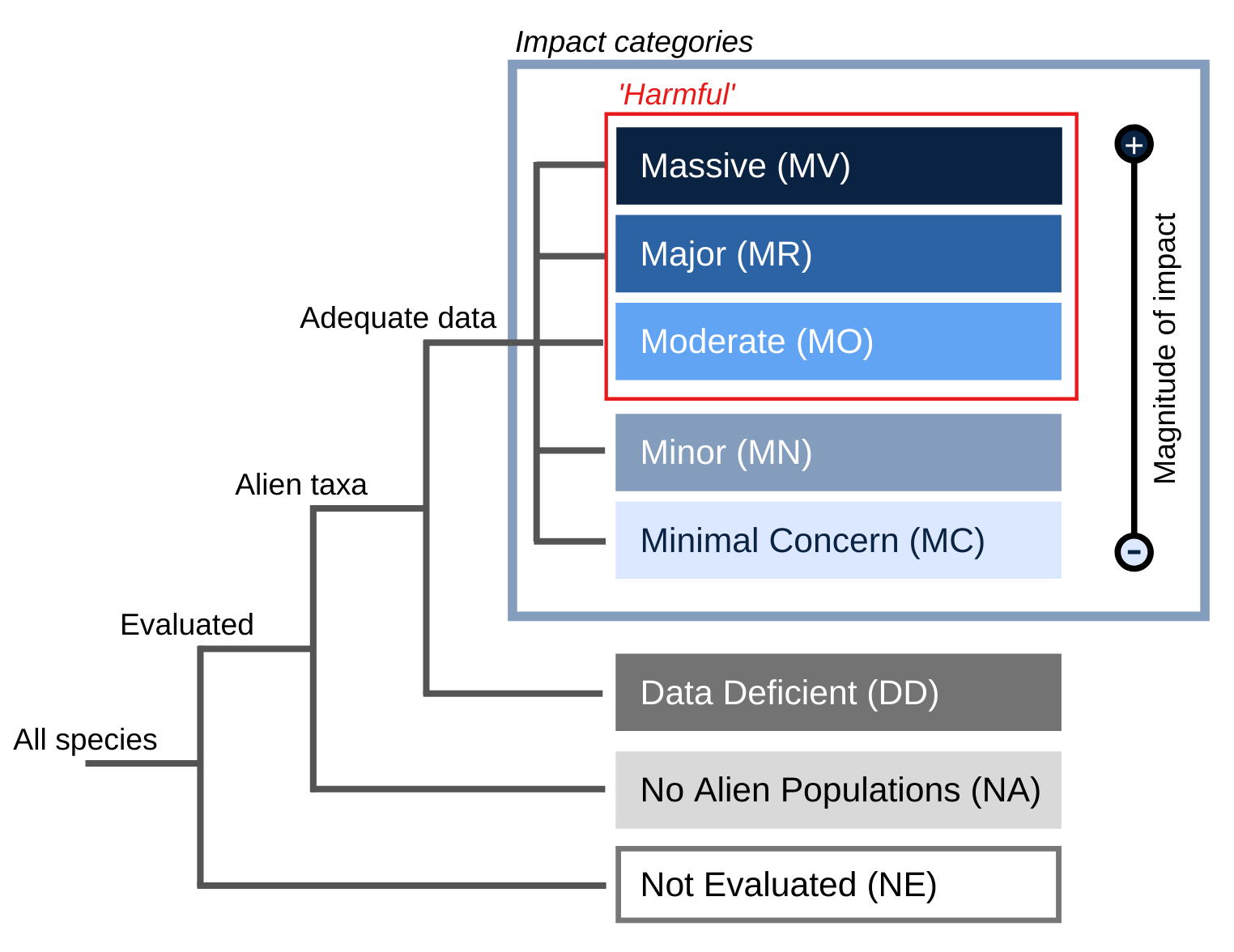

- Impact

- Management

- Bibliography

- Contact

Mesembryanthemum edulis

“Active growth of C. edulis occurs primarily along the main axes, although lateral branches may also grow, particularly following death of the apical meristem of the main axis. An individual branch can elongate more than 1m in a year. Branches tend to grow over each other, resulting in the accumulation of up to 40cm of live and dead plant material. Stems exhibit vine like growth and can crawl over shrubs, fences and other obstacles. Rooting occurs at nodes in contact with the soil surface” (D’Antonio, 1990a). The plant is readily cloned by rooting stem fragments that contain at least one node.

Principal source:

Compiler: National Biological Information Infrastructure (NBII) & IUCN/SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG)

Review: Carla D'Antonio Professor Ecology, Evolution & Marine Biology University of California, Santa Barbara USA

Publication date: 2008-11-09

Recommended citation: Global Invasive Species Database (2026) Species profile: Carpobrotus edulis. Downloaded from http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/speciesname/Carpobrotus+edulis on 02-02-2026.

Physical: Manual methods appear to be the most effective means of controlling C. edulis at this stage. Albert (1996; in PIER, 2005) recommends: \"Hand-pull individual plants and remove any buried stems. Mulch to prevent re-establishment. Large mats can be removed by rolling them up like a carpet\". It is important to remove any C. edulis remains during eradication, as any remains left in place become a focus of regeneration, due to the large number of seeds which survive in the fruit for a long time (Fraga et al. 2006).

Another thing to keep in mind following removal of C.edulis is that secondary plant invaders can take advantage of opened areas, spreading rapidly and impeding restoration efforts in coastal dune habitats. C. edulis leaves behind a layer of debris of dead and decaying organic matter that accumulates under the plant. This tends to be left behind after C. edulis is removed. Within the debris are often the dormant seeds of invasive grasses, and these sprout after C. edulis is removed, benefiting from the accumulation of nutrients in the area that C. edulis has facilitated. To avoid this it may be best to selectively remove C. edulis to ensure that some is left behind to stabilise the soil and minimise sand movement into the area. Once the area has been restored to a more natural community, the remaining C. edulis can be removed and that area restored in turn (Kim, undated).

Chemical: PIER (2005) suggest the use of glyphosate herbicides. Schmalzer and Hinkle (1987) reported that there had been no comprehensive survey of herbicide effects on C. edulis. It is assumed that broad spectrum herbicides would kill C. edulis but they may also impact adjacent vegetation. Chlorflurenol, a morphactin, has been used to reduce growth of C. edulis along roadways (Hield and Hemstreet, 1974; in Schmalzer and Hinkle, 1987).

Biological: The options for biological control are currently limited, as the pathogens which attack C. edulis are not specific to it. Verticillium wilt can cause considerable damage (McCain et al. 1974), but using it could cause problems as it also attacks commercial crops (Schmalzer and Hinkle, 1987). Suehs et al. (2004b) state that a constraint on seed production or germination would be the most efficient way to control C. edulis on a long-term basis, if possible, due to its high success in these domains. Two introduced scale insects caused widespread mortality of Carpobrotus edulis plantings in California in the 1970s (Donaldson et al. 1978). As a result the California highway Department introduced natural enemies to control iceplant scale (Tassan et al. 1982). Nonetheless, scale insects have been observed to cause death of clones in California and could be more widely promoted in natural settings.