- General

- Distribution

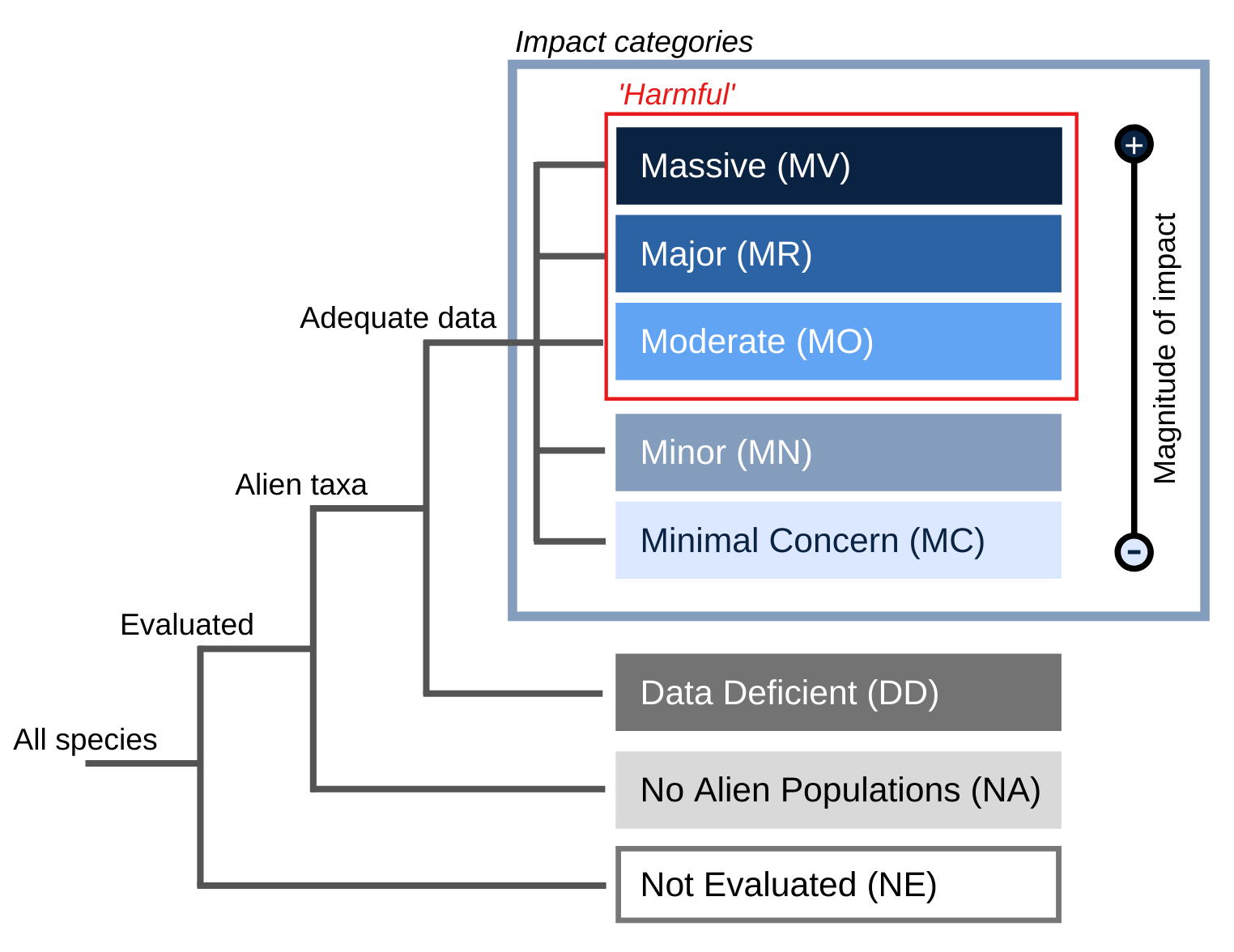

- Impact

- Management

- Bibliography

- Contact

Principal source:

Compiler: Dr Rachel Standish & IUCN/SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG)

Review: Dr Rachel Standish

Publication date: 2005-12-30

Recommended citation: Global Invasive Species Database (2026) Species profile: Tradescantia fluminensis. Downloaded from http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/speciesname/Tradescantia+fluminensis on 22-01-2026.

\r\nPhysical: Hand weeding and rolling the weed up like a carpet are considered suitable for removal of small infestations (Porteous, 1993; C. Buddenhagen, pers. comm., 2001), if care is taken to remove every last piece. In heavily infested forest remnants, gaps left by removal of T. fluminensis are likely to be filled by other invasive species (Standish, 2002a).

\r\nChemical: Chemical control by herbicides is considered a practical means of controlling large infestations of T. fluminensis (McCluggage, 1998). However, re-spraying is often necessary (Standish, 2002a). Furthermore, one of the most widely used herbicides (active ingredient triclopyr) could have detrimental effects on wildlife (Standish et al. 2002b).

\r\nBiological: Cattle and chickens eat T. fluminensis (Timmins & Mackenzie 1995; pers. obs.) but damage other forest plants and the soil in the process. T. fluminensis has been identified as a good candidate for biological control in New Zealand because it is widespread, and the risk of non-target effects are minimal to non-existent (Standish, 2001) and a research programme is underway (S. Fowler, pers. comm., 2003). Reducing both the weed’s biomass and re-invasion of other weeds are the biggest challenges for a biocontrol programme to overcome (Standish, 2001). The gradual reduction of T. fluminensis that is likely to occur with biological control may reduce the chance of invasion by other weeds.

Integrated management: A combination of chemical and manual removal methods has been used with success in New Zealand, but has required repeated efforts to ensure continued control (Anon, 1995). The key to successful control of T. fluminensis is to reduce light availability by improving canopy cover that also reduces invasion by other weeds (Standish et al. 2001; Standish, 2002a). This might be achieved by integrating biological control and tree planting to improve canopy cover.