- General

- Distribution

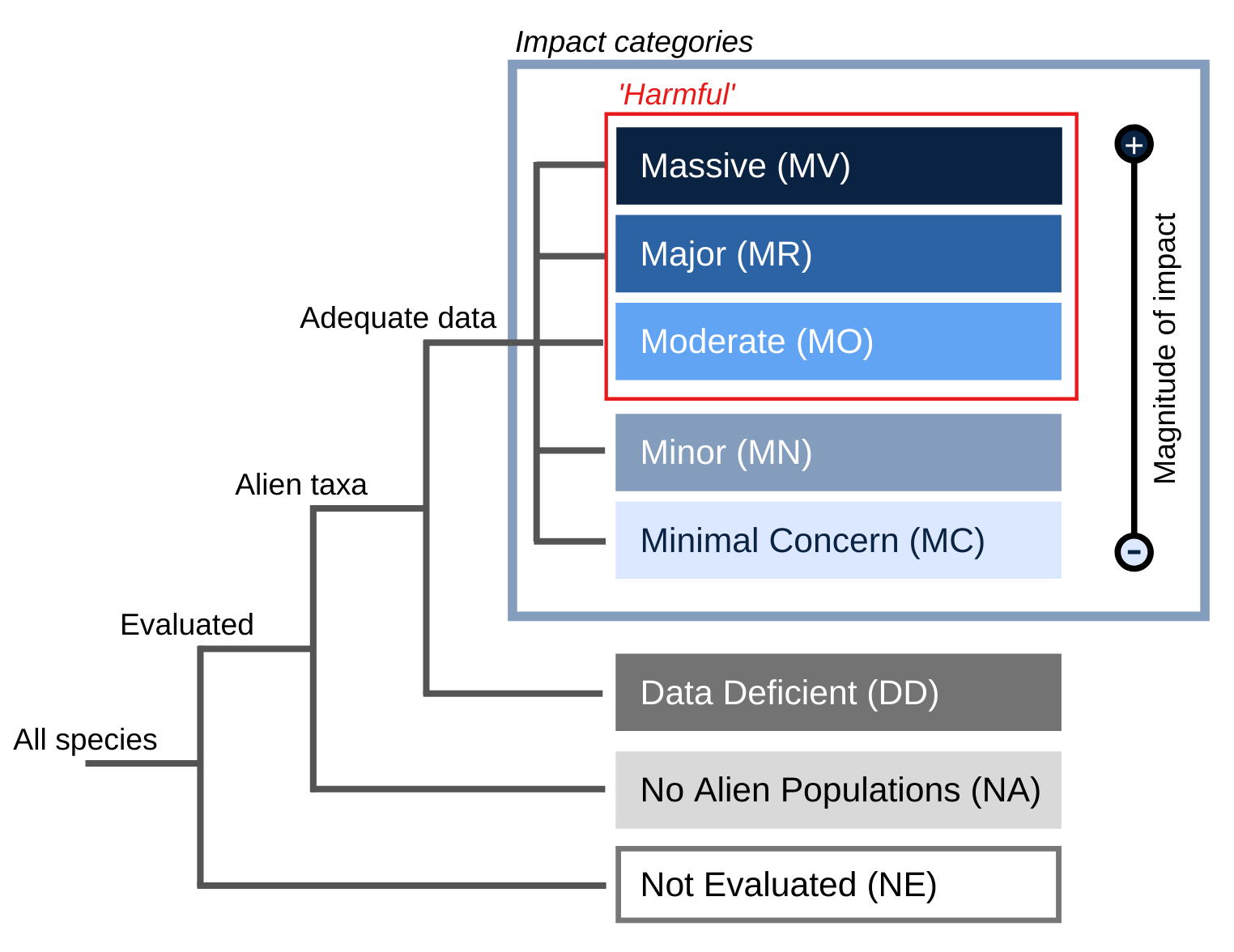

- Impact

- Management

- Bibliography

- Contact

Principal source: Staehr et al. 2000. Invasion of Sargassum muticum in Limfjorden (Denmark) and its possible impact on the indigenous macroalgal community.

Compiler: National Biological Information Infrastructure (NBII) & IUCN/SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG)

Review: Dr. Marit Ruge Bjaerke Section for Marine Biology and Limnology Department of Biology University of Oslo Norway

Publication date: 2005-05-17

Recommended citation: Global Invasive Species Database (2026) Species profile: Sargassum muticum. Downloaded from http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/species.php?sc=727 on 14-02-2026.

Staehr et al. (2000) states that, \"Once established in a new area, S. muticum can accumulate high biomass and may therefore be a strong competitor for space and light. Experiments have indicated that successful settlement and initial development of germlings depend on the availability of cleared substrate with low or no competition from other algae. When first established, however, S. muticum may efficiently prevent settling and development of other algae due to high recruit densities and fast growth. Critchley et al. (1986) showed that the irradiance was reduced by 95% within the uppermost 5cm of a dense S. muticum surface canopy, thus preventing understory algae to develop and thrive.\"

Britton-Simmons (2004) states that, \"Dense S. muticum stands may reduce light, dampen flow, increase sedimentation and reduce ambient nutrient concentrations available for native kelp species. Because kelps are an important source of carbon in coastal food webs and the algal communities they are associated with provide habitat and food for a wide variety of marine animals, any negative effects of S. muticum on these communities may have broader consequences for this ecosystem.\"

Den-Hartog (1997) states that, \"S. muticum is able to replace the eelgrass beds in littoral pools with a mixed substratum of sand, gravel, stones and shell grit. In this way S. muticum restricts considerably the environment where eelgrass beds can maintain themselves as permanent communities.\"

Nyberg and Wallentinus (2005) rank Sargassum muticum eight among 20 highest ranked introduced macroalgae in Europe. The authors study quantitatively ranked species traits which facilitate introduction and predominance using interval arithmetic to search for common patterns among 113 marine macroalgae introduced in Europe. From the abstract Nyberg and Wallentinus (2005) “Three main categories were used: dispersal, establishment and ecological impact. These were further subdivided into more specific categories, a total of 13. Introduced species were compared with the same number of native species randomized from the same families as the introduced. Invasive species (i.e. species having a negative ecological or economical impact) were also compared with non-invasive introductions, separately for the three algal groups. In many categories, as well as when adding all species, the introduced species ranked more hazardous than the native species and the invasive species ranked higher than the non-invasive ones. The ranking within the three main categories differed, reflecting different strategies between the species within the three algal groups. When all categories (excluding salinity and temperature) were summed, the top five risk species, all invasive, were, in descending order, C. fragile spp. tomentosoides, Caulerpa taxifolia, Undaria pinnatifida, Asparagopsis armata and Grateloupia doryphora, while Sargassum muticum ranked eight and Caulerpa racemosa ten. Fifteen of the twenty-six species listed as invasive were among the twenty highest ranked”.

Chemical: Critchley et al. (1986) also reports that, \"The effects of a wide range of herbicides on the growth of S. muticum have been tested and evaluated by Lewey (1976) and Lewey & Jones (1977). However, none of those compounds tested were found satisfactory for use, due to lack of selectivity, the large doses required, the period of time the herbicides need to be in contact with the alga and the problem of chemical application in the marine environment. The most effective herbicides of those tested were Diquat, Stomp, copper sulphate, sodium hypochlorite, K-lox and Nortron. However, all these compounds affected not only S. muticum but also other algae tested.\"

Biological: Critchley et al. (1986) tested a wide range of biological control agents, but found that they were ineffective. Most species that were studied for control would feed on S. muticum but preferred other species more. The authors state that, \"It was concluded that no marine herbivore was likely to restrict S. muticum distribution appreciably within southern England.\"