- General

- Distribution

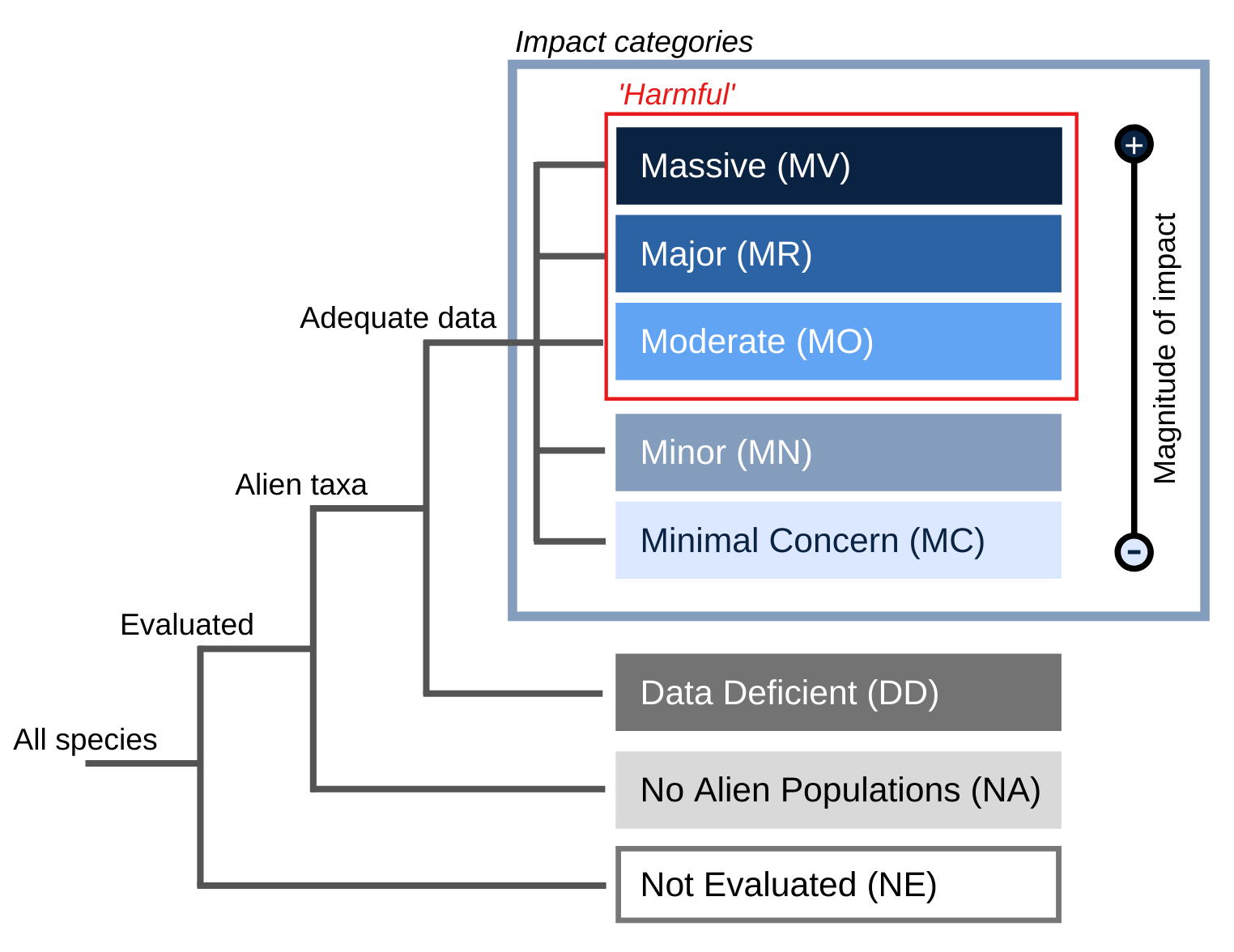

- Impact

- Management

- Bibliography

- Contact

Flowerheads are ovoid, spiny, solitary on stem tips, and consist of numerous, yellow disk flowers. Vigorous individuals of C. Solstitialis may develop flower heads in branch axils. The involucre (phyllaries as a unit) is approximately 12-18mm long. Phyllaries are palmately spined, with one, long central spine and 2 or more pairs of short lateral spines. Phyllaries are more or less densely to sparsely covered with cottony hairs or with patches at the spine bases. The central spines of the main phyllaries are 10-25mm long, stout, and yellowish to straw-coloured throughout. Lateral spines occur typically in 2-3 pairs at the base of the central spine. The corollas are yellow, and mostly 13-20mm long. Flowerheads produce two types of achenes (seeds), both glabrous, approximately 2-3mm long, and with broad bases. Achenes are barrel-shaped, compressed, and laterally notched at the base. Flowers at the periphery of the flowerheads produce dull, dark brown (often speckled with tan) achenes that are darker and have no pappus (the bristly, feathery, or fluffy perianth whorl crowning the ovary). This seed type represents between 10 and 25% of the total seed and often remains in the seedheads until late fall or winter. The central flowers produce glossy, gray, or tan to mottled cream-coloured and tan seeds with a short, stiff, unequal, white pappus (2-5mm long). This represents the majority of seed produced (75-90%).

Principal source: Element Stewardship Abstract for Centaurea solstitialis L. (DiTomaso, 2001) SPECIES: Centaurea solstitialis (Zouhar, 2002)

Compiler: National Biological Information Infrastructure (NBII) & IUCN/SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG)

Review: Dr. Joseph M. DiTomaso, Weed Science Program, Department of Vegetable Crops, University of California, Davis, USA

Publication date: 2005-12-30

Recommended citation: Global Invasive Species Database (2026) Species profile: Centaurea solstitialis. Downloaded from http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/species.php?sc=263 on 01-03-2026.

\r\nPhysical: Mowing can be used as a mechanical option for control provided it is well timed and used on plants with a high branching pattern. Cultural control options include grazing, prescribed burning, and re-vegetation with competitive species. Burning should be timed to coincide with the very early C. solstitialis flowering stage; at this time, it has yet to produce viable seed, whereas seeds of most desirable species have dispersed and grasses have dried to provide adequate fuel. Fire has little, if any, impact on seeds in the soil. In addition to controlling C. solstitialis, burning will reduce the thatch layer, expose the soil, and recycle nutrients held in the dried vegetation. Re-vegetation programs using perennial grasses or legumes can be effective for management of C. solstitialis, but establishment may be difficult in areas without summer rainfall.

\r\nChemical: Clopyralid and picloram (not registered in California) are the most effective herbicides for full season control of the weed. Unlike most post-emergence herbicides, they provide both foliar and soil activity. The best timing for application is when C. solstitialis is in the early rosette stage. Clopyralid gives one season of control and is generally used at 110gm a.e./ha; 290gm product/ha. Picloram has longer soil residual activity than clopyralid (two to three years) and is applied at 0.28kg and 0.42kg a.e./ha. Glyphosate is a non-selective herbicide that is also effective on C. solstitialis. It will control bolted plants at 1.1kg a.e./ha; 9.4 liters product/ha or 1% solution and can be used as a late season spot treatment to small infestations or escaped plants.

\r\nBiological: Sheep, goats, or cattle are effective in reducing C. solstitialis seed production when grazed after plants have bolted but before spines form on the plant. Goats will eat the plant even in the spiny stage. Six biological control agents of C. solstitialis have been imported from Europe and are well established in the western United States. Of these, most effective are the hairy weevil (Eustenopus villosus) and the false peacock fly (Chaetorellia succinea). These insects attack the flower/seed head, and directly or indirectly reduce seed production by 43 to 76%. They do not, by themselves, provide sustainable management of C. solstitialis but can be an important component of an integrated approach. The most widely studied pathogen for C. solstitialis control is the Mediterranean rust fungus, Puccinia jaceae. It can attack the leaves and stem of C. solstitialis, causing enough stress to reduce flowerhead and seed production. The organism is currently under investigation and has not been released for use.