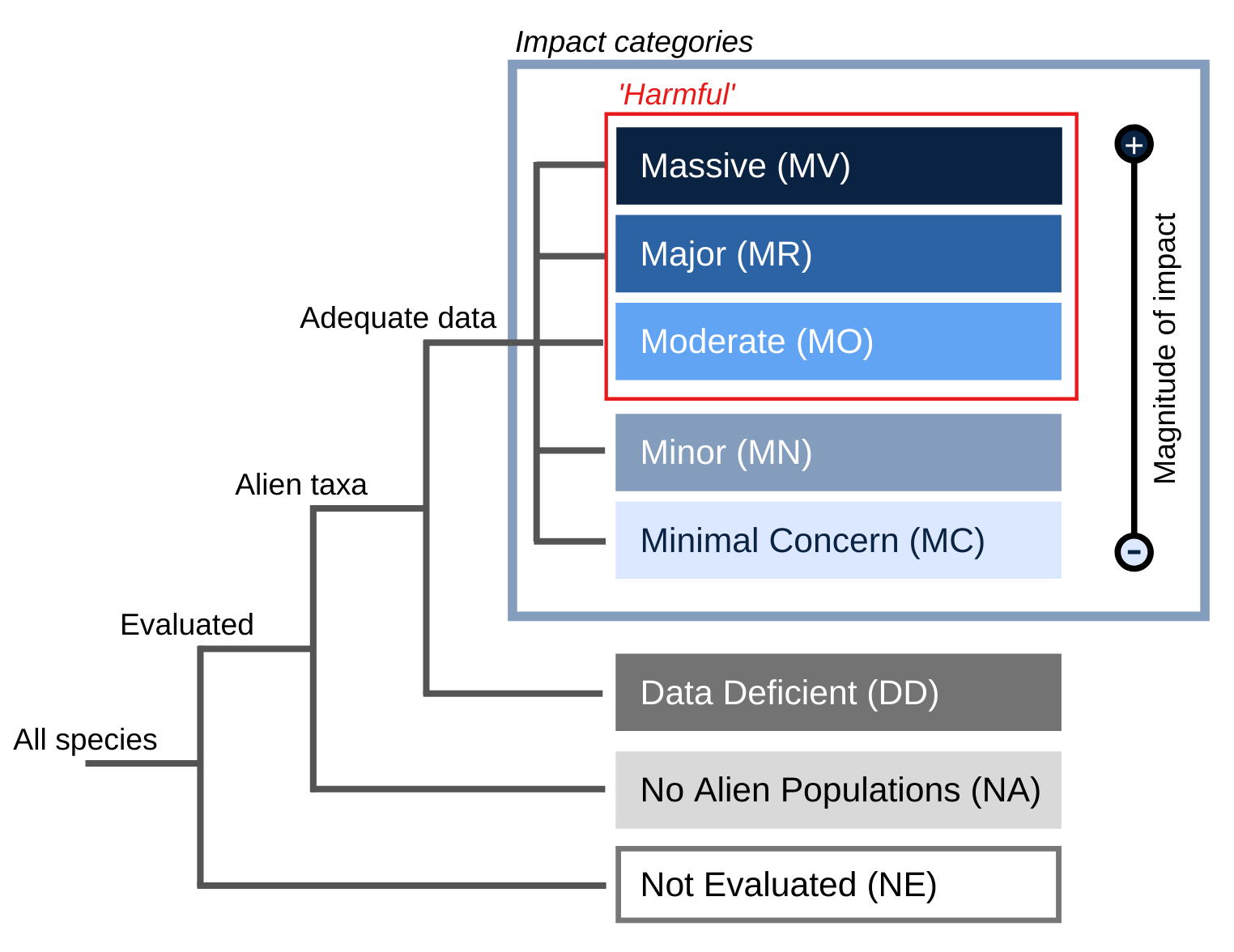

- Not Evaluated

NE - No Alien Population

NA - Data Deficient

DD - Minimal Concern

MC - Minor

MN - Moderate

MO - Major

MR - Massive

MV

- General

- Distribution

- Impact

- Management

- Bibliography

- Contact

Purple swamphen eggs vary in shape, texture, and color; they may be long, oval, or elliptical; the surface may be smooth, glossy, or slightly rough; eggs come in an array of colors such as pale green, yellow-stone, creamy-white, pink, spotted, blotched, maroon, purple, and violet (eggs found in south Florida have been tan with brown spots) (Source: Pearlstine & Ortiz 2009).

In their native range, purple swamphens are known to be very vocal, with a repertoire of calls that includes a common, trumpeting call with a nasal rattle - quinquinkrrkrr - and a wide variety of groans, wails, squawks, shrieks, and hums (Johnson & McGarrity 2009). When displayed, their long and powerful song consists of nasal rattles that crescendo and is territorial in nature (Pearlstine & Ortiz 2009). Purple swamphens are quite terrestrial and will walk and climb readily but don't usually swim (Pearlstine & Ortiz 2009). They can be seen flying between areas in rice fields where groups are present (Pearlstine & Ortiz 2009).

In the Mediterranean region, the species is highly dependent on lowland fresh or brackish water wetlands with abundant emergent vegetation, such as reedmace (Thypha sp.), reeds (Phragmites sp.) and sedges (Carex sp.) (Cramp & Simmons 1980, del Hoyo et al. 1996, Sanchez-Lafuente et al. 1992 2001, as cited in Pacheco & McGregor 2004). In New Zealand the swamphen (or pukeko) is often seen on roadsides, in wetlands or near drainage ditches (Brown et al. 1986, Jamieson 1994, as cited in Washington et al. 2008).

Principal source: BirdLife International 2009. Porphyrio porphyrio. In: IUCN 2010. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species

Doss, D. Paramanantha Swami; Gopukumar, N.; Sripathi, K., 2009. Breeding Biology of the Purple Swamphen (Porphyrio porphyrio) at Tirunelveli, South India. Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 121(4). DEC 2009. 796-800.

Johnson, S.A. and M. McGarrity. 2009. Florida's Introduced Birds: Purple Swamphen (Porphyrio porphyrio). Florida Cooperative Extension Service Publication WEC 270.

Pearlstine, E. V & J. S. Ortiz, 2009. A Natural Histroy of the Purple Swamphen (Porphyrio porphyrio) WEC272. Gainesville. Institute of Food and Agriculture Services

Compiler: National Biological Information Infrastructure (NBII) & IUCN/SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG)

Review:

Publication date: 2010-07-20

Recommended citation: Global Invasive Species Database (2026) Species profile: Porphyrio porphyrio. Downloaded from http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/species.php?sc=1702 on 05-01-2026.

Purple swamphens are known to be highly territorial and aggressive, and often fight amongst themselves and with other species over food (Johnson & McGarrity 2009). In large numbers, these aggressive invaders could have negative impacts on native birds (Johnson & McGarrity 2009).

A recent introduction to Florida, the purple swamphen has expanded from coastal southeast Florida into the Everglades Conservation Areas, and has been observed on Lake Okeechobee. Its ecological similarity to the native common moorhen (Gallinula chloropus) and purple gallinule (Porphyrula martinica) have prompted efforts to eliminate this member of the rail family (Hardin 2007). It is not clear what negative consequences could result from the presence of non-native species such as these, but Avery and Moulton (2007) argue that while the opportunity exists to remove them from the Florida landscape, it should be done. It makes little sense to wait and study the situation to see what impacts might accrue. As management action is delayed, populations of these species will increase and spread, making it that much more difficult and expensive to implement effective corrective measures later (Simberloff 2003, in Avery & Moulton 2007).